Unpacking Innovation

Innovation is the silver bullet not a steroid. A lot of people have come to believe that innovation is the cure for a majority of the systemic challenges that plague our organizations and society today such as poverty, corruption and youth unemployment.

What gives this secret sauce its kick?

A BUBBLE OF OPTIMISM

Innovation is the silver bullet not a steroid.

A lot of people have come to believe that innovation is the cure for a majority of the systemic challenges that plague our organizations and society today such as poverty, corruption and youth unemployment. They seem to forget that innovation isn't easy and although over the long term its rewards are staggering, it has the tendency to make people deeply uncomfortable. All innovation processes ultimately inspire such emotion because they stretch people beyond their sweet spot thereby fundamentally altering them. However, this silver bullet is often interchangeably used as a steroid. In the near term, any effort to introduce innovation will deliver visible results but with time these benefits taper off giving way to behavior from faulty conditioning.

All innovation must be human centric if you want it to stick.

Our faulty conditioning has led us to believe that the enjoyment is supposed to come only after all the work has been done.

— Susan Jeffers (@SusanJeffers) January 24, 2014

Innovation provides leverage.

People and institutions are currently being subjected to an enormous amount of pressure to act and jump on the Innovation bandwagon. However, the primary purpose of innovation has always been to derisk a particular entity by building structural barriers. These barriers exist in a variety of formats such as patents, business models, user experience design, etc. but all of them prolong or acquire domain leadership by leveraging control of market forces. Innovation for its own sake is a luxury today and will never garner support.

A MEASURE OF THE FUTURE

“…about 40% of people just are not going to be good at innovating regardless of what they do. And 5% are born with the instinct.”

If the situation is indeed as bleak as Clayton Christensen estimates then it would be fair to assume that most innovative individuals are concentrated at senior management levels because this quality has been institutionalized as top-down. Thus, it is imperative that these leaders view innovation in the context of a timestamp for business.

Businesses should ideally be concerned about 3 fundamental timestamps on a daily basis. They are -

- The next 2 years

- The next decade

- The next century

These timestamps are important because they push innovation to the background and instead focus the conversation on pertinent issues such as product roadmap, design trends, market consolidation, etc.

Each of these factors are of varying interest when viewed on their own but as part of the larger timestamp framework they serve as abstraction lenses for innovation to thrive.

What features do we need to introduce to match consumer expectations? How will we deliver the next version of this experience? How do we intend to stay relevant to our target audience? What has the potential to make us redundant? What can we do to leapfrog all our competitors? What role do we want to play in our consumers lives? Is there any way we can fully meet their unexpressed needs? What would it take to reach the perfect solution? How else can we delight our consumers?

If any management is able to confidently tackle these sort of questions across the 3 timestamps then I have absolutely no reason to doubt their ability to sustainably inculcate innovation into their business culture.

THE FOUR FACES OF INNOVATION

All innovations are grounded in context such as regulations, environmental conditions, market forces, etc. but are subsequently unified by four faces or characteristics. These faces help us to distinguish real innovation from best practices and also aid our shared understanding of their mechanics.

Not all innovations are created equal.

Clayton Christensen has masterfully elaborated on incremental and exponential innovation, also known as sustaining and disruptive innovation, but this face still offers substantial opportunities for exploration. I have elaborated on a few of the principal mechanics below -

Anything that can be commoditized, productized and platformized, eventually will be, in that order.

This is a core tenet of innovation and thus the natural progression of incremental innovation is to accelerate trends to the point that they become ubiquitous. Beyond this point, evolution flatlines and requires a disruption to occur through process, paradigm or application in order to substantially move forward.

Furthermore, since innovation is a human quality it is subject to the herd effect and thus concentrates itself in areas of intense public interest - real and perceived. Its potency is usually found to be dependent on maturity of industry, market size, stage of innovation, etc. but innovation gradually redirects to other areas in accordance with the law of least resistance.

Innovation and markets are friends and foes.

Innovation and markets have always shared a paradoxical relationship.

If we were to define research as the process to convert money into knowledge then innovation would naturally follow as the converse of it. The hypothesis at the root of this definition is that commercial success is the only true metric for innovation. This isn't always true since free markets have historically undervalued disruptors in mature industries. In addition to this, strong export and commodity economies have demonstrated a reduced ability to innovate since disruption by a market leader would predicate economic cannibalism.

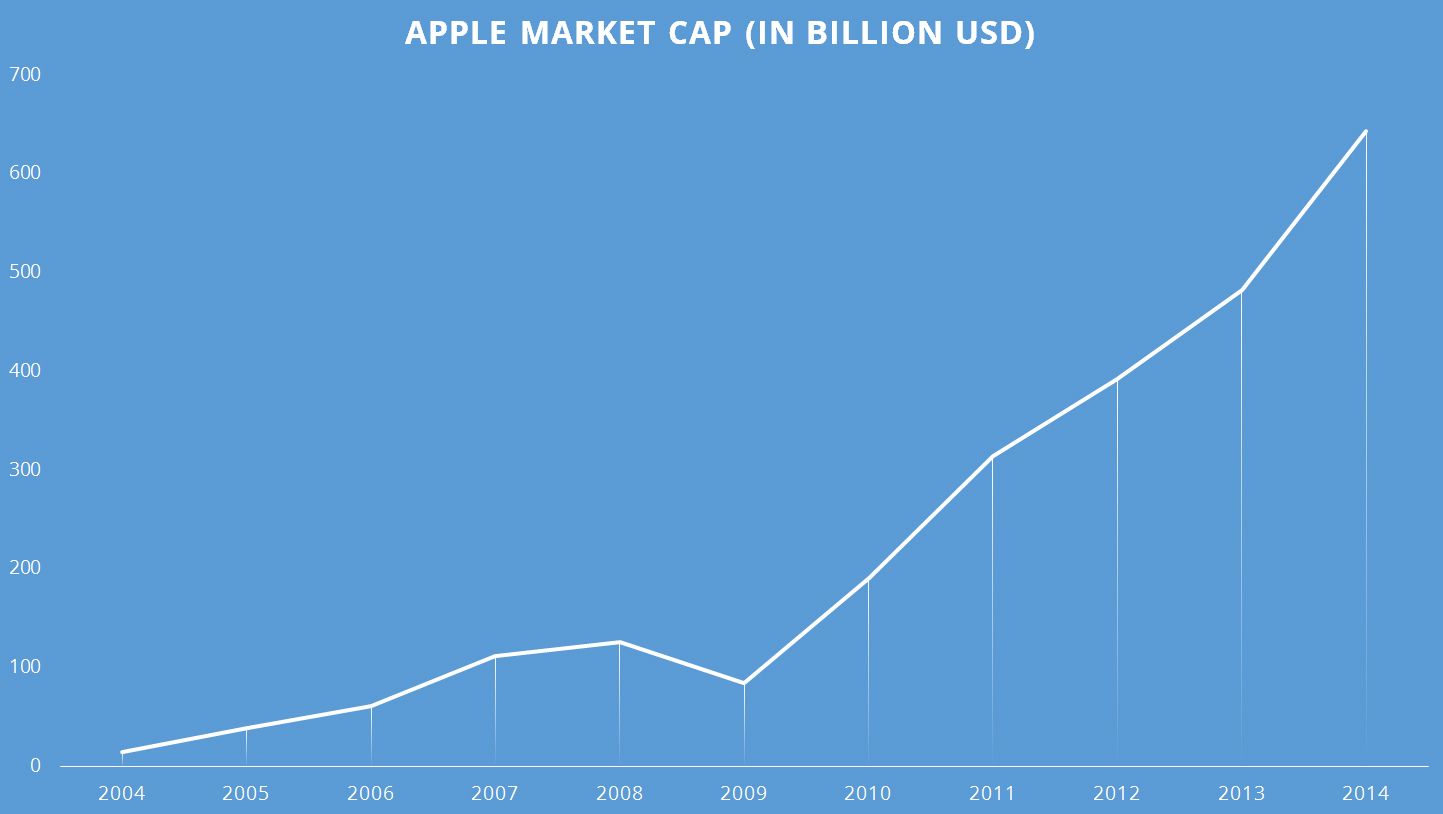

Although innovation and market success appear to be contrary to each other, they are in fact strongly correlated since the former contributes to the latter. Apple is a great example of this because its choice to develop transformational products such as iPhones and iPads was tacit approval to cannibalize on its iPod and Mac lines. This decision was responsible for accelerating Apple’s market capitalization from roughly $14 billion in 2004 to more than $640 billion in 2014.

Practicing innovation is managing innovation.

Considerable amounts of time and energy have been devoted to developing an ethos or mindset that promotes innovation and creativity but little attention has been paid to the process of managing it. There is a growing realization in institutions that this procedural void is in fact the major challenge in incorporating innovation as an organizational trait.

In my opinion, innovation management has 3 primary pillars. They are —

1. Locus of Control: All innovation may be aimed at internal or external audiences and although both are important it is critical for an innovation portfolio to achieve its unique balance since they face wildly different challenges, and offer rewards and require resources which are highly time dependent. However, this quest for balance should not be misconstrued for weakness in differentiation or divisiveness.

2. Human Linkage: Organizations and products are essentially a work in progress and thus they are subject to usual human constraints such as performance pressure, resource utilization challenges, motivation issues and a broken management system. There are several strategies to tackle these issues but all of them are dependent on establishing the human link. Storytelling, gamification and shared ownership are all examples of tactics which breed an entrepreneurial self-help mindset where the conversation moves from deliverables and rewards to meaningful questions around effort and creativity such as - How can all of us work harder together? How can all of us work better together? What do we want our future to look like ?

3. Portfolio Hedging: This technique is frequently employed by bankers to minimize the negative impact of adversity in one member or investment of the portfolio by relying on another. It can be applied to the management of an innovation portfolio as well by relying on the standard levers of change - time, money, synergy and contrarian selection. Hedging of innovation risks through proper budget asset allocation has seen adoption but as a macro tool it remains in its infancy.

Innovation is a multi-stakeholder exercise.

Innovation always has 4 primary stakeholders -

1. Leaders

2. Regulators

3. Disruptors

4. Audiences

In this exercise, the core mechanic is -

Leaders establish context. Regulators establish rules.

Disruptors establish choice. Audiences establish order.

Thus the market leader establishes the context for the industry as well as future trends, and regulators draft appropriate rules for managing the industry in its present avatar. However, the onus for innovation and introducing choice rests with the disruptor, in response to whose actions the audiences reestablish public order and market value. Thereafter the incumbent market leader and regulator must respond suitably and catch up with the disruptions. The exercise is cyclical and continues till a systemic equilibrium is achieved.

Although the exercise is a dramatic oversimplification of reality it was conjectured to pose probing questions to all stakeholders. Some of these are -

Is the role of the regulator solely limited to establishing rules? If not, how should it enable other stakeholders to perform their roles better or introduce new actions? Are structured programs, services and utilities the only viable options? How can society shift to culturally accept entrepreneurship and innovation on an everyday basis? How can market leaders sustain competitive advantage in today’s world?

There will always be more questions than answers but real world experiments such as Ecuador’s Free, Libre, Open Knowledge (FLOK) Society to transition to a post-capitalist peer to peer economy, should be observed very closely to understand the nuances and implications of multi-stakeholder innovation at scale.